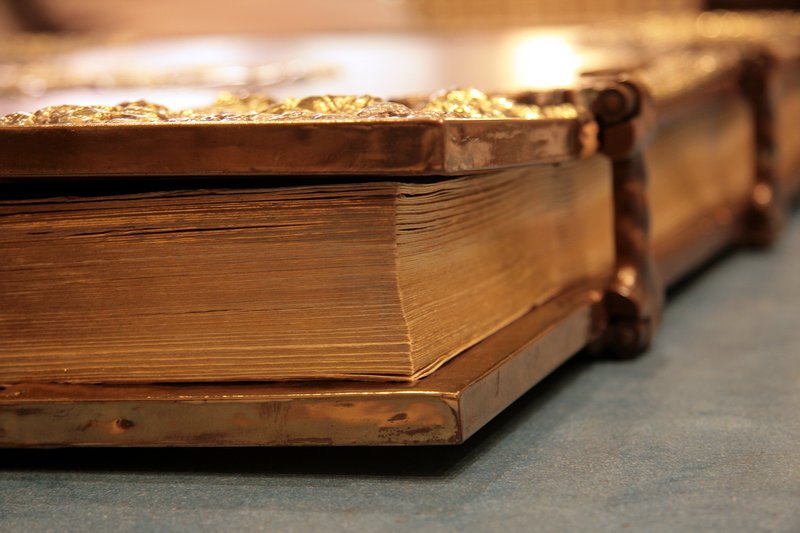

NETZACHT: MAIN READING FOR THIS WEEK – FOR MITZVOT – And There Was Evening and There Was Morning

And There Was Evening and There Was Morning

Article No. 36, 1984-85

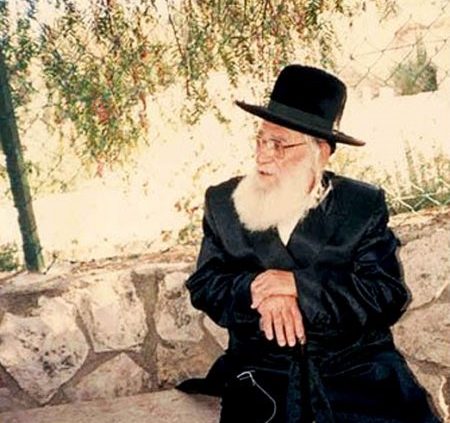

Rabbi Baruch Shalom HaLevi Ashlag ( The Rabash )

The Zohar says about the verse, “And there was evening and there was morning” (Genesis 3, p 96, and Item 151 in the Sulam Commentary), “‘And there was evening,’ which the text writes, means that it extends from the side of darkness, meaning Malchut. ‘And there was morning’ means that it extends from the side of the light, which is ZA.

“This is why it writes about them, ‘One day,’ indicating that the evening and morning are as one body, and both make the day. Rabbi Yehuda said, ‘What is the reason?’ He asks, ‘Since ‘And there was evening and there was morning’ points to the unification of ZON, that the light of day comes out of both of them, then after the text announces it on the first day, why does it says about each day, ‘And there was evening and there was morning’?’

“And he replies, ‘It is to know that there is no day without a night and no night without a day, and they will never part from one another. This is why the text repeats and informs us each and every day, to indicate that it is impossible that there will ever be the light of day without the darkness of night. Likewise, there will never be the darkness of night that does not bring a day after it, since they will never part from one another.’” Thus far its words.

We should understand the above-written in the work, as to what light means and what darkness means, and why it is impossible to have a day unless it is from the both of them together, meaning that light and darkness produce a single day, that is, it takes both to build a single day. This means that the day begins when the darkness begins because this is when the sequence of the making of a new day begins.

We should also understand how the word “day” can be applied to darkness, since when the darkness has begun, we can already begin to count the day.

It is known that after the restrictions and the departure of the light that occurred in the upper worlds—after the second restriction and the breaking—the system of Klipot [shells] emerged, until the place of BYA divided into two discernments. From its middle and above it was the BYA of Kedusha [holiness], and from its middle and below it became the permanent section of the Klipot, as explained in TES (Part 16, p 1938, Item 88).

Consequently, in this world, “A man is born the foal of a wild donkey” and he has no desire for spirituality. Thus, from where does the sensation of need for spirituality come to a person, to the point of saying that he feels darkness, which he calls “night,” by feeling that he is remote from the Creator? We must know that at the same time he begins to feel that he is far from the Creator, he is already beginning to believe in the existence of the Creator to some extent, or else, how can he say that he is remote from something that doesn’t exist? Instead, he must say that he has some illumination from afar that shines for him to the extent that he feels that he is remote from the Creator.

It therefore follows that as soon as the darkness begins, meaning the sense of the existence of darkness, the light immediately begins to shine to some extent. And the measure of illumination of the light is recognized only through negation. That means that one feels a lack, that he does not have the light of the Creator shining for him in an affirmative manner. However, the light shines for him in the form of lack, meaning that now he begins to feel that he is missing the light of the Creator, which is called “day.”

But those for whom the light of day does not shine don’t know if there is such a reality where a person must feel the absence of the light of the Creator, which is called “day.” Let us speak of a single person, meaning within the same body. Sometimes one feels that he is in darkness, meaning that he is remote from the Creator and craves to draw near to the Creator. He feels suffering at being remote from the Creator.

The question is, “Who causes him to worry about spirituality?” And sometimes he feels darkness and suffering when he sees that another is successful in corporeality in possessions and with people, while he lacks both sustenance and respect. He sees about himself that in truth, he is more gifted than the other, both in terms of talent and in terms of ancestry, and he deserves more respect. But in fact, he is many degrees lower than the other one, and this pains him terribly.

At that time, he has no connection to spirituality, and he doesn’t even remember that he ever was connected, and that he himself considered all the friends with whom he was studying at the seminary, that when he saw them suffering for their concerns to achieve wholeness in life, they seemed to him like children who cannot make a purposeful calculation, and all that their eyes see is what they want. At one time they see that the most important thing in life is money, and at another time they see that the most important thing in life is to have a respectable position among people, etc.. And now he is within those very things that he mocked, and he feels that his life is tasteless unless he determines the whole of the hope and peace in life at the same level that they determine, that this is called “life’s purpose.”

And what is the truth? It is that now the Creator has taken pity on him and illuminated the discernment of day for him, and this day begins with negation. In other words, when the day begins to shine in his heart in the form of darkness, it is called “the beginning of the rise of day,” and then Kelim begin to form in him, in which the light will be able to shine in an affirmative manner. This is the light of the Creator, when one begins to feel the love of the Creator and begins to feel the flavor of Torah and the taste of Mitzvot.

From this we can understand the above words of The Zohar, that a day comes out specifically of the both of them, as it writes, “This is why it writes about them, ‘One day,’ indicating that the evening and morning are as one body, and both make the day.” Also, when Rabbi Yehuda said that this is why the text alerts every day anew—to indicate that it is impossible that there will ever be light without the darkness of the night that comes first. And also, there will not be the darkness of the night that does not bring the light of day after it, so they will never part from one another.

It is as mentioned above, 1) following the rule that there is no light without a Kli, and 2) it also requires light, which is called “day,” to make a Kli.

But we should understand why, if one has already been granted a little bit of day in the negative form and feels that his whole life is only if he is rewarded with Dvekut with the Creator and he begins to torment over being remote from the Creator, who, then, causes him to fall from his state of ascent? In other words, his whole life should be only in spiritual life, and this is all his hope, and he suddenly falls into a state of lowliness, a state where he would always laugh at people whose hope in life was to obtain the fulfillment of beastly lusts. But now he himself is among them, nourished by the same nourishments that they feed on.

Moreover, we should wonder how he has forgotten that he was once in a state of ascent. Now he is in a state of such amnesia that it doesn’t even occur to him that he would consider the people that he is now among, meaning that his only ambitions are at such a low level and he is not ashamed of himself that he dared go into such an atmosphere that he always ran from. In other words, this air that they breathe so willingly, he would always say that it suffocates Kedusha [holiness], and now he is among them and feels that there is no fault in them.

The answer is as the writing says (Psalms 1), “Happy is the man that has not walked in the counsel of the wicked.” We must understand what is the counsel of the wicked. It is known that the question of one who is wicked that is brought in the Hagadah [Passover narrative] is “What mean you by this service?” Baal HaSulam explained that it means that when a person begins to work in order to bestow, the wicked one’s question comes and asks, “What will you get out of not working for yourself?”

And when a person receives such a question, he begins to contemplate that perhaps he is right. And then he falls into his net. Accordingly, we should interpret, “Happy is the man that has not walked in the counsel of the wicked” that when the wicked come to him and advise him that it is not worthwhile to work if he does not see some benefit and gain from it to himself, he does not listen to them. Instead, he strengthens himself in the work and says, “Now I see that I am going on the path of truth, and they wish to confuse me.” It follows that when that man overcomes, he is happy.

Afterwards, the writings says, “Nor stood in the way of sinners.” We should interpret “Way of sinners.” He says, “Nor stood.” A sin is as we explained in the previous essay (35, 1984-85), that the sin is if a person breaks “You shall not add.” In other words, the real way is that we have to go above reason, called faith. And the opposite of that is knowing—the body understands that he has no other choice except to believe above reason.

Hence, when he feels some taste in the work and takes it as support, and says that now he does not need faith, since he already has some basis, he immediately falls from his degree. And when one is careful about it and does not stand for even a minute to look and see if it is possible to change his basis, it is considered that he is happy because he did not stand in the way of sinners, to look at their way.

And afterwards, the writing says, “Nor sat in the seat of the scornful,” referring to those people who spend their days idly, who do not take their lives seriously and consider every moment precious. We should know to what “The seat of the scornful” refers. Those who cherish every moment and sit and think of others—if other people are all right and how much others should correct their actions, and have no pity for themselves, worrying about their own lives, this causes them all the descents. The RADAK interprets scornful as being of a shrewd mind in an evil way, finding faults in people and disclosing secrets to each other. This matter is for lazy people, idlers. This is why he said, “Nor sat in the seat of the scornful,” and this is the reason for the descents.

SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA-SHACHARIT שַחֲרִית MORNING PRAYER

SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA-SHACHARIT שַחֲרִית MORNING PRAYER SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA-TIKKUN CHATZOT תקון חצות-TIKKUN RACHEL & TIKKUN LEAH

SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA-TIKKUN CHATZOT תקון חצות-TIKKUN RACHEL & TIKKUN LEAH SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA- KABBALAH MED-TIKKUN CHATZOT תקון חצות – LESSON WITH RAV MICHAEL LAITMAN

SUNDAY PRAYER: HOCHMA- KABBALAH MED-TIKKUN CHATZOT תקון חצות – LESSON WITH RAV MICHAEL LAITMAN